Marty Glickman

The Fastest Kid On The Block

Authors: Marty Glickman, Stan Isaacs

Published: Syracuse University Press, 1999

A Reflection by Nat Asch

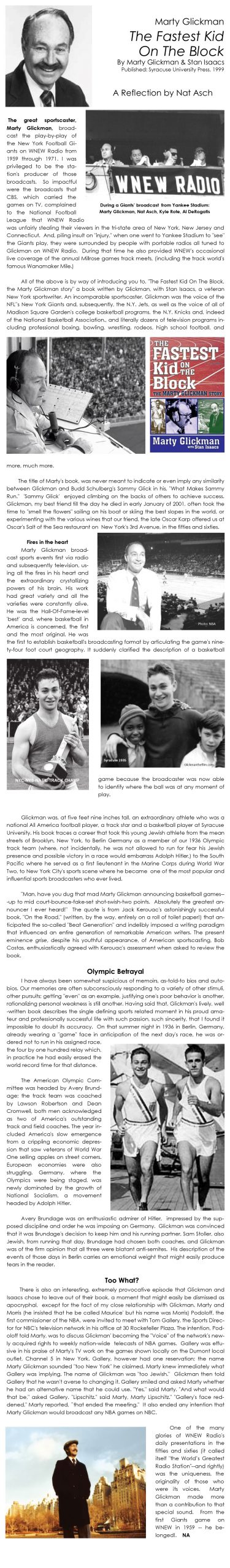

The great sportscaster, Marty Glickman, broadcast the play-by-play of the New York Football Giants on WNEW Radio from 1959 through 1971. I was privileged to be the station’s producer of those broadcasts. So impactful were the broadcasts that CBS which carried the games on TV, complained to the National Football League that WNEW Radio was unfairly stealing their viewers in the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut! And, piling insult on “injury,” when one went to Yankee Stadium to “see” the Giants play, they were surrounded by people with portable radios all tuned to Glickman on WNEW Radio. During that time he also provided WNEW’s occasional live coverage of the annual Millrose games track meets, (including the track world’s famous Wanamaker Mile.)

All of the above is by way of introducing you to, “The Fastest Kid On The Block, the Marty Glickman story” a book written by Glickman, and Stan Isaacs, a veteran New York sportswriter. An incomparable sportscaster, Glickman was the voice of the NFL”s New York Giants and, subsequently, the N.Y. Jets, as well as the voice of all of Madison Square Garden’s college basketball programs, the N.Y. Knicks and, indeed of the National Basketball Association., and literally dozens of television programs including professional boxing, bowling, wrestling, rodeos, high school football, and more, much more.

The title of Marty’s book, was never meant to indicate or even imply any similarity between Glickman and Budd Schulberg’s Sammy Glick in his, “What Makes Sammy Run.” ‘Sammy Glick’ enjoyed climbing on the backs of others to achieve success. Glickman, my best friend till the day he died in early January of 2001, often took the time to “smell the flowers” sailing on his boat or skiing the best slopes in the world, or experimenting with the various wines that our friend, the late Oscar Karp offered us at Oscar’s Salt of the Sea restaurant on New York’s 3rd Avenue, in the fifties and sixties.

Fires in the heart

Marty Glickman broadcast sports events first via radio and subsequently television, using all the fires in his heart and the extraordinary crystallizing powers of his brain. His work had great variety and all the varieties were constantly alive. He was the Hall-Of-Fame-level ‘best’ and, where basketball in America is concerned, the first and the most original. He was the first to establish basketball’s broadcasting format by articulating the game’s ninety-four foot court geography. It suddenly clarified the description of a basketball game because the broadcaster was now able to identify where the ball was at any moment of play.

Glickman was, at five feet nine inches tall, an extraordinary athlete who was a national All America football player, a track star and a basketball player at Syracuse University. His book traces a career that took this young Jewish athlete from the mean streets of Brooklyn, New York, to Berlin Germany as a member of our 1936 Olympic track team (where, not incidentally, he was not allowed to run for fear his Jewish presence in a race would embarrass Adolph Hitler,) to the South Pacific where he served as a first lieutenant in the Marine Corps during World War Two, to New York City’s sports scene where he became one of the most popular and influential sports broadcasters who ever lived.

“Man, have you dug that mad Marty Glickman announcing basketball games—up to mid court-bounce-fake-set shot-swish-two points. Absolutely the greatest announcer I ever heard!” The quote is from Jack Kerouac’s astonishingly successful book. “On the Road,” (written, by the way, entirely on a roll of toilet paper!) that anticipated the so-called “Beat Generation” and indelibly imposed a writing paradigm that influenced an entire generation of remarkable American writers. The present eminence grise, despite his youthful appearance, of American sportscasting, Bob Costas, enthusiastically agreed with Kerouac’s assessment when asked to review the book.

Olympics Betrayal

I have always been somewhat suspicious of memoirs, as-told-to bios and autobios. Our memories are often subconsciously responding to a variety of other stimuli, other pursuits; getting “even” as an example, justifying one’s poor behavior is another, rationalizing personal weakness is still another. Having said that, Glickman’s lively, well-written book describes the single defining sports related moment in his proud amateur and professionally successful life with such passion, such sincerity, that I found it impossible to doubt its accuracy. On that summer night in 1936 in Berlin, Germany, already wearing a “game” face in anticipation of the next day’s race, he was ordered not to run in his assigned race, the four by one hundred relay which, in practice had easily erased the world record time for that distance.

The American Olympic Committee was headed by Avery Brundage; the track team was coached by Lawson Robertson and Dean Cromwell, both men acknowledged as two of America’s outstanding track and field coaches. The year included America’s slow emergence from a crippling economic depression that saw veterans of World War One selling apples on street corners. European economies were also struggling. Germany, where the Olympics were being staged, was newly dominated by the growth of National Socialism, a movement headed by Adolph Hitler.

Avery Brundage was an enthusiastic admirer of Hitler, impressed by the supposed discipline and order he was imposing on Germany. Glickman was convinced that it was Brundage’s decision to keep him and his running partner, Sam Stoller, also Jewish, from running that day. Brundage had chosen both coaches. and Glickman was of the firm opinion that all three were blatant anti-semites. His description of the events of those days in Berlin carries an emotional weight that might easily produce tears in the reader.

There is also an interesting, extremely provocative episode that Glickman and Isaacs chose to leave out of their book, a moment that might easily be dismissed as apocryphal, except for the fact of my close relationship with Glickman.. Marty and Morris (he insisted that he be called Maurice’ but his name was Morris) Podoloff, the first commissioner of the NBA, were invited to meet with Tom Gallery, the Sports Director for NBC’s television network in his office at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. The intention, Podoloff told Marty, was to discuss Glickman’ becoming the “Voice” of the network’s newly acquired rights to weekly nation-wide telecasts of NBA games. Gallery was effusive in his praise of Marty’s TV work on the games shown locally on the Dumont local outlet, Channel 5 in New York. Gallery, however had one reservation; the name Marty Glickman sounded “too New York” he claimed. Marty knew immediately what Gallery was implying. The name of Glickman was “too Jewish.” Glickman then told Gallery that he wasn’t averse to changing it. Gallery smiled and asked Marty whether he had an alternative name that he could use. “Yes,” said Marty. “And what would that be,” asked Gallery. “Lipschitz.” said Marty, Marty Lipschitz.” “Gallery’s face reddened,” Marty reported, ˇthat ended the meeting.” It also ended any intention that Marty Glickman would broadcast any NBA games on NBC.

One of the many glories of WNEW Radio’s daily presentations in the fifties and sixties (it called itself “the World’s Greatest Radio Station”–and rightly) was the uniqueness, the originality of those who were its voices. Marty Glickman made more than a contribution to that special sound. From the first Giants game on WNEW in 1959 — he belonged!

Nat Asch

Marty Glickman – The Fasted Kid On The Block www.syracuseuniversitypress.syr.edu/books-in-print